The Connection

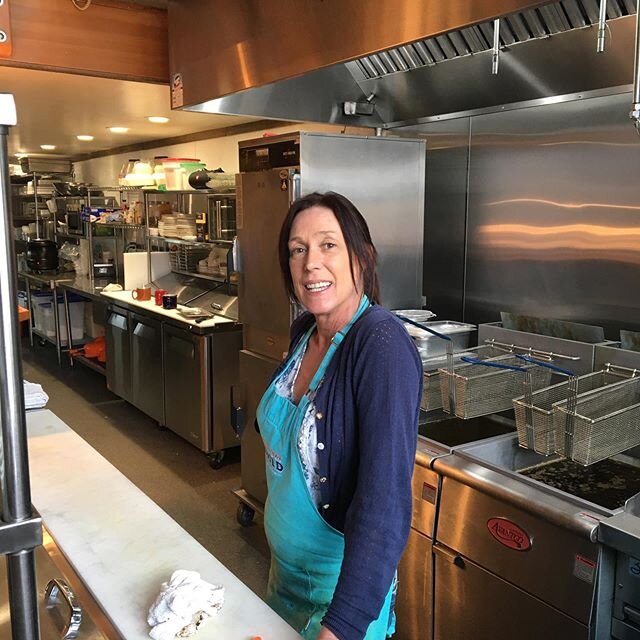

/Pat and Kessler on Pats boat Veronika K

“I wrote The Connection years after it happened. I remember in the writing, the biggest struggle was to represent the events as honestly as I could – I didn’t want my son to feel minimized in the story whatsoever, even though that’s what I was doing to him within the story. I wanted my inability to understand his point of view to be the true obstacle between us, as it is with so many parents about so many issues. Once Veronica (his mom) intervened, I had no choice but to hear him. He was in his twenties, a grown man and on his own when I sent the story to him...besides his mother, he was the first person to see it. I needed his stamp of approval before I sent it out into the world. To my relief he told me the story accurately portrays events as he remembers them too. His mom is the hero of the story, even though she plays a small part, her role is the most important one. I hope you enjoy it. ”

The Connection

The season is winding up, and as my deckhand, I look to you for help.

“Tomorrow’s the first big day,” I remark as we head out to the net rack. “We have to get this gear on today and go for groceries. I’d like to head out tonight.”

Your face falls, but I haven’t noticed.

“I’m not feeling so good,” you answer, and I see your scowl. I’m in my skipper mentality, what your mother calls my “jerk mode,” so I’m quick to assume the worst: I think you just don’t want to work. After all, I think, you’re 13, and though you like making money, you’d rather play video games than help out. It’s just my first wrong assumption of the day.

By the time I chew on that for a while, I’m angry at you. We work with the gear in silence. I stew over what to do. I need the help, but I don’t need the distraction of an attitude. You committed to working for me for the season, and I want to teach you to live up to your commitments. Isn’t that what being a Dad is all about?

I’m even more upset, and we haven’t spoken a word. You go through the motions, but the tension between us is thick. We’ll argue this out later, after the nets are on the boat. We drive to the cannery in a thick cloud of dust and silence.

Home, hours later, after dinner, I’m starting to pack up. “Got your gear together?” I ask, knowing you haven’t.

“I don’t feel good,” you answer from your bed. “My stomach hurts and I’ve got a headache.”

“Look,” I say, walking into your room, “I need your help tomorrow. I’m sorry you feel bad, but you promised me you’d come, and we need to get going. We have to get out of the river before the tide is too low. Take some Tylenol for your headache. You can sleep on the boat.”

“I don’t think I can do it, Dad!” Your voice rises as you start getting upset. “Can’t you just go without me?”

“No,” I answer, my voice getting louder, too. “I need you tomorrow. I’m counting on you.” I walk out of your room and down the hall toward mine. “It’s gonna be a big day, and we really need a third hand to pitch the fish, and that’s you. Come on. We don’t have time to argue!”

“No, Dad!” you yell back at me, coming out into the hall. “I can’t go! I don’t feel good!” You run back into your room and slam the door.

“What the hell? I mutter under my breath. “I don’t have time for this.” Your Mom, hearing the loud voices, comes down the stairs. “What is wrong with him?” I start with her, “Is he…?”

“Hold on a minute, she says softly, stopping me. “He knows how big a day it is tomorrow. Something else is going on.” She heads toward your room.

“Wait,” I say. “Let me.” I walk into your room and see your body under the covers, facing the wall, lights off, shades drawn. “Hey,” I say, trying to sound calm. “What’s really going on? Why don’t you want to go?”

“ I TOLD YOU! I DON’T FEEL GOOD!” You pull the covers tighter. “LEAVE ME ALONE!”

Angry all over again, I yell back, proving I can yell louder, “HEY! Just get dressed and let’s go! Stop this ACT! Get out of bed NOW! Come ON!”

I raise my arms in exasperation as I march out of your room and down the hall again. Veronica just stares at me as I stomp by. She turns quietly and disappears into your room.

I’m angry, embarrassed and confused. I throw my clothes into my day bag like they were trash. I can’t BELIEVE this. Not now, not TODAY. I shake my head. Tomorrow is forecasted to be big, and could make the difference in how we do for the season. It’s too late to get anyone else, and I need the help! Why are you doing this?

I hear voices coming out into the hall. I step into the doorway to see you, tears running down your cheeks standing in front of your mother. She says gently, “Go on. Tell him. It’s ok.”

“Dad,” you say, with a look that goes right to my core, “I don’t want to go. I don’t want to do it.” You stop for a breath and look down. “I just can’t stand all the killing.”

…and I am no longer in the hallway with you. I am on the back deck of the first boat I fished on, the North Sea. Fishing my first season as a crew, no longer a 48-year-old skipper with two children, but 27 years old and as green as can be, I am watching hundreds of salmon come over the stern, and I am stunned at all the death. Some of the fish come aboard already dead; most of them will die soon; some struggle, some accept it, some are puzzled. Some actually look like they know what’s happening and are resigned to their fate. If fish are like people, I think, then it’s in this: they die in as many ways as we. But the part that’s hardest to accept is that I am partly responsible for their deaths. Confronted with this terrible sense of guilt and shame, I come closer to quitting fishing forever on this day than on any other for the next twenty years.

How could I not hear you?

My anger and frustration melt like ice in the sun. “I understand.” I say softly, because suddenly I do. “I understand completely.” We hug and talk. I tell you of that day, and how I had a hard time with the killing too. I explain the nature of it, how I came to understand I was harvesting a source of healthy food just as the fish were at the end of their lives anyway. You listen. We arrive at a compromise.

“So you’ll help with boat work when we get back to the dock?”

You nod and look very serious. “Yes. I ‘d like that.”

“It’s a deal. See you tomorrow.”

I lean over and give you a hug goodnight. Standing at the foot of your bed, arms folded, your mother looks at us, and smiles.

#

The connection was first published by The Journal of Family Life online, July, 2009, and most recently in Anchored in Deep Water: The FisherPoets Anthology - Family Dynamic.